INNOVATION

How Health Systems Can ‘Humanize’ Data to Affect Real Change

Stacey Mueller likes to use the example of Chipotle to highlight how “humanizing” data can drive change for all organizations, including health systems.

As the Executive Director of Experience Management at Froedtert & The Medical College of Wisconsin describes it, the fast-food chain and others in that industry “have dialed into ‘the vital few’ and developed a model that balances what consumers want—in this case, personalization of the dish they are eating, healthy choices as well as commitments to the ethical treatment of animals—with a cost-conscious array of ingredients.”

She continues, “Health care is not a burrito, and the lesson here isn’t about what’s in the steam table. Chipotle is developing a deep understanding of customer values and lifestyles … [and how they fit] into the bigger picture of their lives.”

Similarly, she adds, “we need to know more about how our patients and potential patients think about health, wellness, and health care within the frame of their day-to-day lives.”

To do so, health care leaders should expand their approach to patient and consumer segmentation by incorporating psychographic personas—or profiles based on how individuals think, make decisions, and behave—rather than relying solely on demographic data such as age, race, and gender to define patient preferences and needs.

This deeper understanding of behavioral motivations, according to Mueller and John McKeever, the Chief Growth Officer with health care management consulting firm Endeavor Management, enables organizations to tailor communications, services, and engagement strategies more effectively.

During a session at the SHSMD Connections Conference in September 2024, Mueller and McKeever shared the experience of Froedtert & The Medical College of Wisconsin’s use of psychographics. The hospital’s program was launched in 2021 and, within a year, gained valuable insights and built a roadmap for integrating these personas across marketing, patient experience, and care delivery, they say.

Psychographics: A Summary

Psychographics has been defined as the study, observation, and categorization of people based on their attitudes, aspirations, and other psychological criteria. The approach has proved particularly valuable in market research.

McKeever describes psychographics as helping organizations “connect to an organism … knowing the emotional/functional needs ... of the communities” they serve.

There are essentially three steps to the psychographic process:

Step 1: Surveying the audience. For health systems, this means asking patients about their attitudes and behaviors with regard to their health, in addition to demographic questions. It also involves getting as deep a sense as possible about how these same patients feel about the health system and its providers.

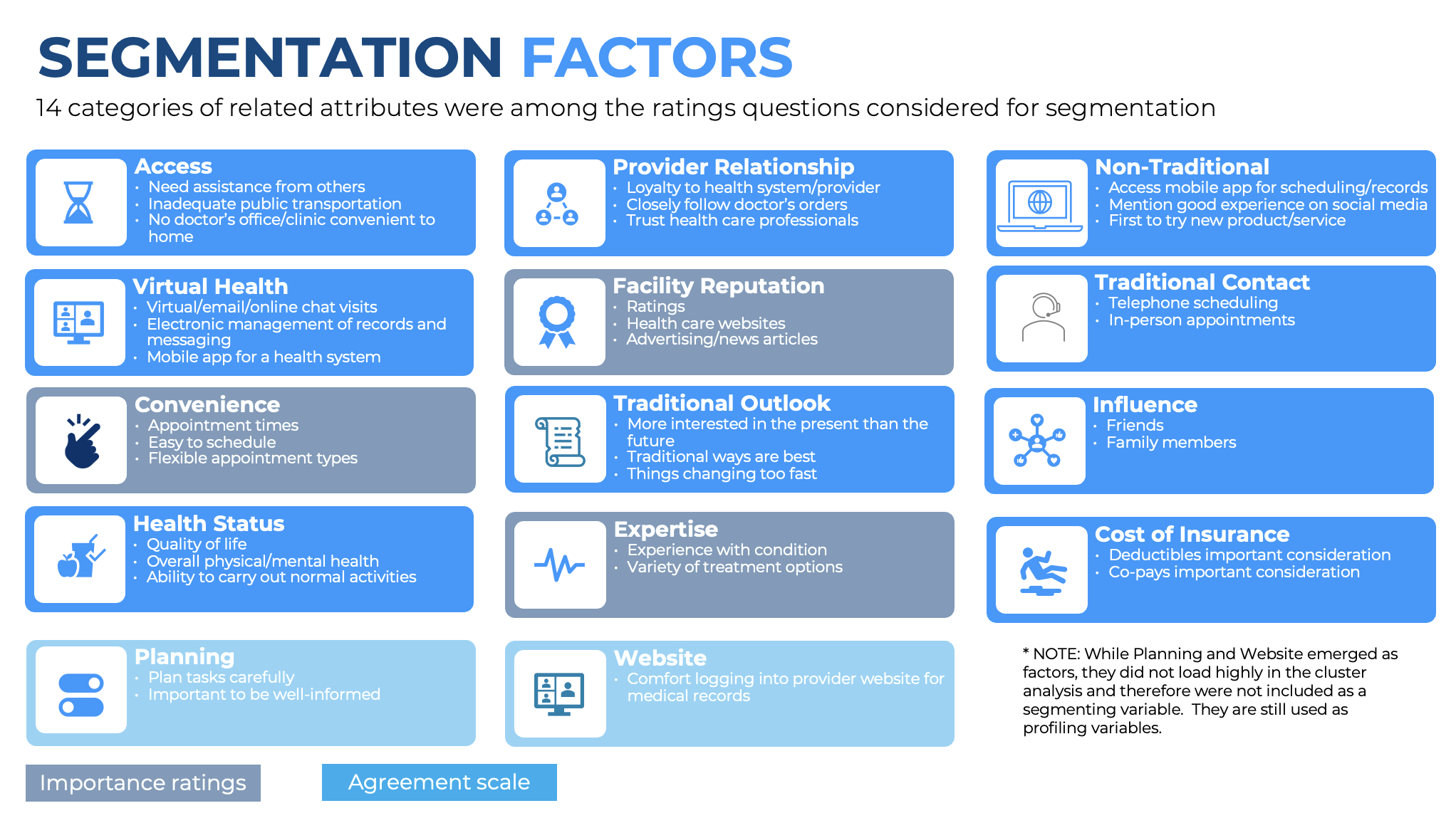

Step 2: Identifying variables. All collected data need to be interpreted to pinpoint critically differentiating variables that can be used to classify patients. Froedtert & The Medical College of Wisconsin considered 14 “categories of related attributes” for segmentation, Mueller says. These included attitudes and preferences related to access (i.e., whether patients need assistance from others to visit the hospital, or whether there’s adequate public transportation), provider relationship (i.e., loyalty to patients’ health systems/providers, and whether they closely follow doctors’ orders and trust their health care professionals), and current health status.

Step 3: Synthesize into segments. Once the data have been collected, health system must identify four to six key variables and use analytical techniques to group patients with similar traits. The resulting segments represent distinct patient personas, enabling more personalized and effective marketing campaigns.

The Results

To start the process, in April 2021, Froedtert & The Medical College of Wisconsin surveyed 728 adults 18 years of age and older in its catchment area, which includes 10 counties surrounding Milwaukee.

Segmentation factors such as convenience and reputation were assessed based on “importance ratings” (i.e., how much value respondents gave them), while others such as provider relationship and the availability of virtual health services were evaluated using an agreement scale, according to McKeever (Figure).

Based on the responses, the team developed artificial intelligence–generated avatars—a collection they called a “persona family”—that represented the most common “personalities” with Froedtert & The Medical College of Wisconsin’s patient base. Examples include “Attuned Alex,” who is described as an “informed … digital enthusiast,” and “Value-Seeking Val,” who is cost-conscious and seeks convenience.

These personas helped the health network identify its high-priority patient segments, and the goals, behaviors, and needs of those in these groups. They also enabled the hospital to pinpoint these patients’ “sources of influence [and] their role in the buying process,” according to Mueller.

Mueller recalls: “Receiving the deliverables from the segmentation research was like being handed a bunch of newborn infants. Now what?”

The health network’s first step was to engage its care teams in group discussions of the newly identified personas/segments and how they can and should influence the services it provides and its patient communications.

The health network also used the information to change the ways in which patients could access care services and communicate with their providers.

Of note, the information it gathered was less about typical “descriptive demographics” and more focused on the “story” driving patients and their preferences, McKeever says.

In short, the approach enabled Froedtert & The Medical College of Wisconsin to really “get to know” its patients, not as numbers or statistical trends but as people, Mueller explains.

The health network integrated these new patient personas into its subsequent consumer experience research, marketing initiatives, patient communications, and care processes, ultimately driving more personalized, meaningful interactions with patients and improved outcomes.

“Once we had the persona type data attached to our patient data set, we thought, ‘What could we learn through quantitative analysis about health care consumption habits and patterns? What would we see if we applied psychographic segmentation to our basic patient experience data?” Mueller says. “What if we could apply predictive analytics to offer care team members real-time suggestions about what a patient might need in terms of decision support, based on the psychometric persona type?”