INNOVATION & CROSS-DISCIPLINARY SOLUTIONS

Planning for the Future of Health Care Needs Requires Rethinking Patient Needs

Anticipating the needs of future patients, and understanding how to best engage them, is a delicate process that requires communication, innovation and planning. Doing this effectively may force you and your colleagues to rethink existing strategies in order to better connect with existing patient needs and avoid being surprised by future developments.

“How we start thinking about what our future patients want and need, and how we start designing for their needs now is key, so that we aren’t surprised in five or 10 years when the world has passed us by because we haven’t been doing our homework,” says Denise Worrell, Principal, Innovation and Transformation at Langrand, in Houston. Worrell spoke during a session at the SHSMD 24 Connections Conference in October.

Such study reflects Worrell’s background as an academically trained futurist and her position as an adjunct professor in the University of Houston’s Foresight Master’s Program.

What is foresight?

“The way I like to explain it to people is that history is the study of the past and foresight is the study of the future,” Worrell notes. “The point of foresight is to help organizations understand the possible and probable futures that are ahead of them, and how they can start making decisions in the present so they are not surprised later.”

Studying and understanding potential future scenarios puts organizations in a position to be actively steered toward futures that will be beneficial, and away from those that may hinder their performance and goals.

Key to understanding how this works involves a concept called “The Three Horizons,” which states that over time the ways in which people do things today will no longer strategically fit in the market like they once did.

“Over time, that strategic fit erodes; and at the same time, there are new ideas, paradigms and innovations that are emerging and eventually take over,” Worrell explains. “So, when I say that as a futurist I study the future, what I’m really doing is looking for pockets of the future that exist today, and understanding patterns of change and which are most likely to win out.”

In the middle of this shift toward future models falls a period of ambiguity, turbulence, and transition as new ideas and approaches are being developed, tested, and slowly make their way into broader society.

A technology currently in the middle of this complex area of ambiguity is telehealth.

“There is a turbulence of clashing values” regarding telehealth, Worrell says, consisting of significant differences between the interests of patients, health care professionals, leadership teams and the companies developing telehealth products.

And while technology, and its adaptation, drives much of this clash of values, generational mindsets also greatly affect how patients see their own needs and what they want out of their health care partners.

“When we think about designing for the wants and needs of future patients, we have to step back and admit we can’t just continue with what made sense for baby boomers,” Worrell explains. “It’s not the same world that younger generations grew up in. This is a really key concept.”

As an example, betting that millennials will want to approach their health care in a similar way to other generations can be a grave miscalculation.

“You are assuming that you know what these younger generations want, and that they are going to be the same values that older generations had,” Worrell notes.

A key example of the millennial and Gen Z influence on the future of health care is their interest in mental health and physical health being given equal weight by health care professionals.

“They feel like their mental health is just as important as physical health, and they expect the health care system to treat them that way,” she adds.

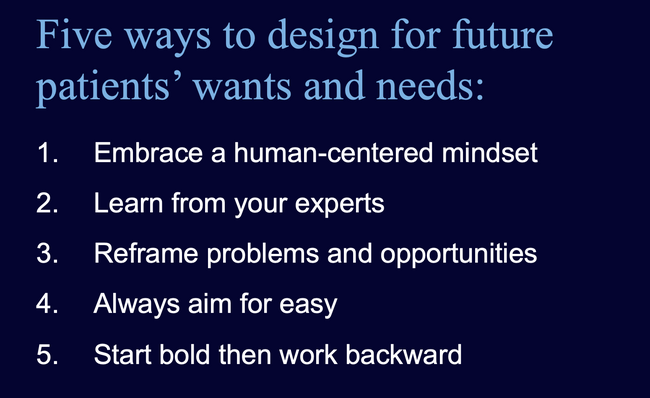

Other trends, such as distrust of institutions, increasing rates of loneliness, and the concept of delayed or late adulting, which results in people choosing not to have children or doing so later in life, will all have significant ripple effects in coming years. To address this, organizations can begin to pivot, focusing on five steps:

- Truly embracing a human-centered, not operations-focused mindset. “Today, much of the mindset in health care is focused on operations,” Worrell notes. “We talk about being patient-centered, but if we stand back and objectively look, most of the time the patient is the last thing that we think about.” Regulations complicate the health care experience, and a reliance on operational goals and marketing efforts often shifts the focus away from what patients actually want. “Instead of asking how do we get people to use our services, we need to start asking how do we make services people want to use,” Worrell advises. “It’s a subtle shift, but it really makes a difference in how you start to design things.”

- Learning from their experts. In the health care space, the most important experts are your patients. While Worrell appreciates groups such as patient advisory councils, or data that can be sourced from surveys, she recommends rolling up one’s sleeves—literally—to observe and interact with patients. “Patients are the ones whose voices have been lost for a long time,” she explains. “You need to understand people and what they need. This may be controversial, but take off your badge and sit in the ER on a Friday night and watch to see what it’s really like to be a patient.” Doing so will provide valuable insights into where real pain points exist within an organization, and may foster honest conversations with patients who are very willing to express how an organization may be failing them.

- Reframing problems and their potential solutions so they are centered on patients’ needs. “The most impactful solutions are created when you put things through [a patient’s] lens versus what you as an organization are trying to do operationally,” Worrell notes.

- Making things easy, allowing for patients to have less complex and more enjoyable experiences. “Always aim to make whatever you are putting together as easy as possible for people,” Worrell suggests. “‘Simple’ wins every time.”

- Starting big and thinking boldly, and then working backward. “Bold beginnings lead to impactful outcomes,” Worrell explains. “It’s easy to take a big idea and break it into pragmatic steps. It’s really hard to take a small idea and try to stretch it into greatness.”

Amid all of this, it’s key to remember that change takes time.

“Change most often looks like an s-curve,” Worrell says. “It can be very slow for a long time, and then there is a technological breakthrough, a new need, or a change in the political environment, which can provide a spark.”

Such is the case with artificial intelligence, which currently feels revolutionary but has actually been in development since the 1950s, according to Worrell. She highlights three key points to remember as you begin to develop new products and services for the future.

“The patients you serve in the future are going to have different values than those you are serving today,” she says. “Serving them well requires really understanding their needs, and keeping an eye on interesting technological and ideological developments will help prevent you from being surprised as the world changes.”